The Largest Graphic Design Movement in Human History

This is the story of the rise and fall of these masterpieces known as Notgeld in five chapters.

In the last years of the German Empire, money didn’t just lose its value; it lost its meaning. Coins vanished, paper collapsed, and whole towns were forced to invent their own currency just to survive. But something unexpected happened. In the middle of this economic chaos, thousands of artists, printers, and small towns accidentally created one of the largest graphic design movements in human history. What began as emergency money turned into a nationwide explosion of colour, storytelling, and desperate beauty.

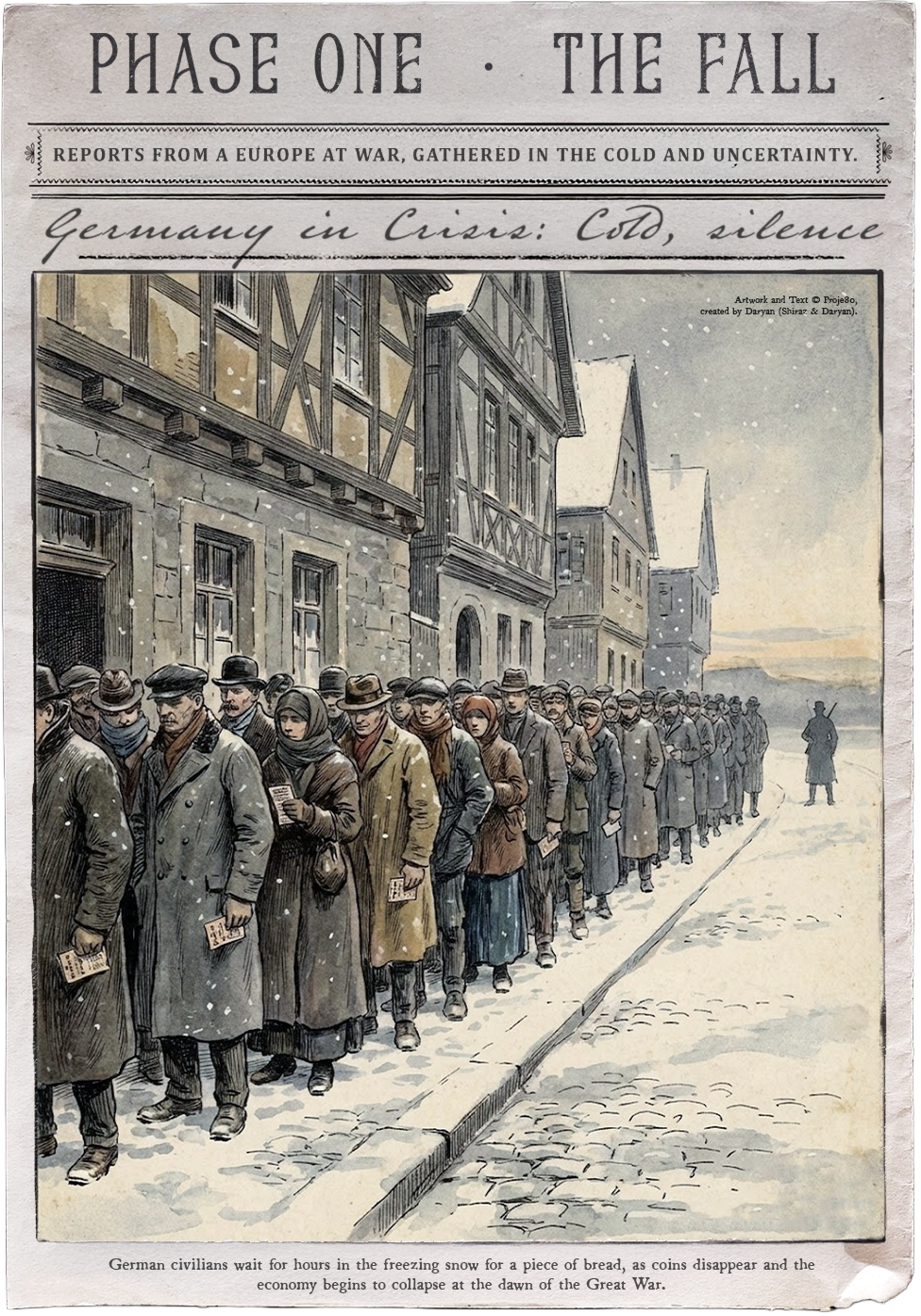

PHASE ONE | The Fall

Before the first piece of Notgeld ever existed, Germany was already cracking from the inside. Years before WWI, the Reichsbank sensed trouble and quietly began stacking gold, preparing for a Europe wide disaster. And then, on a warm late July night in 1914, the first shock of war hit, and the entire system snapped almost instantly.

Gold exchanges were banned. People rushed to the banks and exchanged more than 100 million marks into gold in a single week; the modern value of that amount would be well over 2.62 billion dollars. Silver coins vanished because the metal itself became more valuable than the number printed on the coin. Nickel disappeared next, swallowed by the factories making weapons. By 1916, even the smallest coins were gone, not because they were rare, but because people hoarded anything that felt stable or real.

Paper money was suddenly backed by nothing. No gold, no silver, no anchor, just a government, basically a printed promise saying this has value, even when everyone knew the promise was empty.

Prices doubled. Then tripled. Food was stretched with fillers just to fake the weight. Rationing took over, limiting how much people were allowed to buy because the shortages were so severe. A third of the country’s meals were bought illegally on the black market at prices ten times higher than before the war.

By 1918, Germany had printed eight times more paper money than before the war began. The mark kept sinking against the dollar, and state debt grew so large that the government couldn’t pay the interest anymore. Every corner of daily life was affected. Shops had no change. Markets couldn’t break a note. Workers were paid in paper that lost value every week.

Money still existed on paper, but it no longer worked as money.

And then one day, right in the middle of this collapse, the first Notgeld appeared, not from a bank, not from a government office, but from a brewery in Bremen in July 1914 (Bürgerliches Brauhaus GmbH). Coins were disappearing so fast that the brewery printed its own notes just to keep everyday trade alive. What began as a local emergency fix would soon become something far bigger.

This is the moment the movement begins.

PHASE TWO | The Wave

Once the first emergency notes appeared in 1914, the idea didn’t stay in Bremen for long. Germany was bleeding coins faster than the central bank could replace them, and by 1916 the shortages had reached every corner of the country. Towns, cities, and factories had a choice: shut down daily life or print their own money.

They didn’t wait for permission.

Metal was gone. Silver was gone. Even cheap zinc and iron coins couldn’t be produced fast enough. So local authorities stepped in and started creating their own solutions, handwritten notes, typewritten notes, tiny printed slips, anything that could be passed from one hand to another and trusted for a day or two.

And it worked.

A bakery in one town would accept a note issued by the local council. A coal yard would accept a voucher printed by a nearby factory. Shops began trading them like real currency because they had no other choice.

By late 1916, hundreds of towns were doing this. By 1917, it was thousands.

Notgeld wasn’t an art form yet. Not a collector’s item. It was raw survival and was spreading like wildfire.

Every town printed what reflected its own identity. Some used the town crest. Some used the mayor’s signature. Some had prayers, warnings, or local jokes printed on them. Some were so cheaply made you could see the fibers of recycled paper, old documents, even book pages under the ink.

The country’s monetary system was fragmenting into tiny local islands of money, each one valid only within its own borders. A note from one town might travel a few villages away if someone trusted it, and sometimes these notes moved hundreds of kilometers across Germany as people fled the war, carrying whatever value they had left in their pockets.

Chaos was growing, but it was controlled chaos, the kind that kept the economy breathing.

By 1918, every region of the empire had joined in: Schleswig Holstein, Saxony, Westphalia, Bavaria, Silesia. Each producing its own emergency currency, each slowly developing its own visual language.

Germany no longer had one currency. It had hundreds.

And underneath it all, something unexpected was beginning to form. Printers and artists started noticing how quickly people recognized these little notes. They saw the way locals kept them, traded them, talked about them.

The seed of a design movement had been planted… but nobody knew it yet.

PHASE THREE — The Rise

By the time the war ended in 1918, Germany was exhausted. The empire had collapsed, the mark was sinking, and the country was trying to rebuild itself with a currency nobody fully trusted. But something strange was happening underneath all this chaos. People had started collecting Notgeld.

At first, it was accidental.

Soldiers returning home brought back little notes from the towns they passed through. Civilians kept the more beautiful ones as souvenirs from a time they didn’t want to forget. Museums asked towns to send samples for documentation. Local councils complained that people were keeping the money instead of spending it.

And that’s when towns noticed something important. The prettier the note, the more people believed in it.

It wasn’t official psychology, just basic human instinct. If a note looked cheap, rushed, or ugly, nobody trusted it. But if a note looked cared for, illustrated, coloured, and symbolic, people felt safer using it. Beauty became a form of stability.

Printers and artists understood this quickly.

What used to be rough, rushed paper notes now looked like miniature posters, full of personality and stories. Designers started pushing themselves and each other. A small competition formed between towns. Who could make the most beautiful note? The funniest? The darkest? The most emotional? The most symbolic?

By 1920, the whole country had fallen into this quiet design battle.

Towns released notes in themed series. Some told stories across multiple notes like a mini comic. Some used folklore, mythology, or old medieval legends. Some showed local heroes, factories, churches, battles, tragedies.

The colors got richer. The printing got sharper. The illustrations became bold, sarcastic, tragic, symbolic.

Collectors went crazy. They traveled from town to town asking for new sets. Towns realized this meant money, so they printed even more, sometimes selling them in envelopes with written explanations.

These weren’t emergency notes anymore. They had turned into Serienscheine, collectible series created not to fix the economy but to satisfy the rising hunger for art, design, and storytelling. They pushed early graphic design into places it had never been, tiny pieces of currency acting like posters, postcards, propaganda, comics, and folklore scenes all at once.

This was the turning point.

Notgeld had transformed from a temporary fix into one of the largest graphic design movements in human history. Thousands of towns, thousands of artists, each creating their own visual language at the exact same moment.

And the world hadn’t even seen the craziest part yet.

PHASE FOUR — The Explosion

By 1922, the entire German economy was shaking like a building about to collapse. Notgeld had already spread through every town, factory, and tiny office in the country. But now something far worse arrived: hyperinflation. And it hit so fast that even the emergency money couldn’t keep up.

Prices doubled. Then doubled again. Then doubled again later the same day.

A loaf of bread could cost five marks in the morning and fifty by the afternoon. People were being paid twice a day because waiting until evening meant their salary was worthless. Children made kites out of banknotes because paper money was cheaper than buying toys.

And in the middle of this madness, the central bank completely lost control.

The Reichsbank simply couldn’t print fast enough. They were flooding the country with new notes, but the value evaporated faster than the ink could dry.

So Germany went back to the only system that still worked. Anyone with access to a printing press was allowed to create money.

Cities printed money. Villages printed money. Banks printed money. Factories printed money. Mines printed money. Shops printed money. Even sports clubs and cafés printed money.

Some towns printed millions. Some printed billions. Some printed trillions.

Collectors watched in disbelief as ordinary Notgeld suddenly shifted into massive denominations. Even the artistic Serienscheine were being stamped with desperate overprints:

10 pfennig became 10,000.

1 mark became 1 million.

A small note from a tiny town could suddenly say 500 billion.

People didn’t carry wallets anymore; they carried bags, boxes, and sometimes wheelbarrows full of collapsing paper.

And then came the strangest chapter. Money stopped being printed on paper at all.

Coal companies printed coins made of compressed coal dust. Energy companies printed notes backed by kilowatt hours. Some towns printed money redeemable in wheat, rye, sugar, oats. Wood mills printed notes backed by chopped firewood. Gas companies printed notes backed by cubic meters of natural gas.

These pieces were called Wertbeständige, meaning fixed value money, currency backed by real things instead of numbers.

Reality had broken so completely that Germans were using money made of coal, and sometimes burning it as fuel.

By July 24th, 1923, the central bank officially admitted defeat. By November 15th, 1923, the mark became worthless, not weak, not unstable, but officially zero.

A currency of five hundred years collapsed in a single season.

And in that wreckage, Notgeld reached its absolute peak, thousands of issuers, millions of designs, a visual storm of desperation that the world had never seen before.

But everything that explodes eventually has to settle.

PHASE FIVE — The End

By the end of 1923, the German mark was finally declared worthless.

Zero.

A dead currency.

Almost as suddenly as it had begun, the government shut the whole thing down.

A new currency arrived.

The Rentenmark.

Stable, controlled, gold fixed.

Every town, city hall, brewery, mine, café, bank, and club was ordered to stop issuing local money. The printing presses fell silent.

Finally, on November 12th, 1923, right at the edge of winter, the movement ended overnight.

Notgeld didn’t fade because it lost artistic value. It stopped because the economy forced a hard shutdown. But the work itself survived: tens of thousands of miniature posters, each one carrying a fragment of how people saw themselves, their towns, their fears, and their hopes during the hardest years of their lives.

When hyperinflation ended, all of it became history, not just economic history, but graphic design history.

Notgeld is a diary of a nation printed on paper.

A visual record of fear, humor, pride, collapse, and survival.

A reminder that art doesn’t always come from studios or galleries.

Sometimes it comes from chaos.

The era ended.

But the designs became immortal.

Today, when you hold a piece of Notgeld, you’re not holding old money.

You’re holding the voice of a town... the hand of an artist who never signed their name... and a moment in history when beauty became a lifeline.

A movement born from an emergency.

Shaped by creativity.

Ended by policy.

And remembered through the art it left behind.

Interesting Facts — The Scale of the Movement

1. The number of unique designs is insane

Historians estimate between:

30,000 to 50,000 unique Notgeld designs

Some experts argue it might be closer to 70,000+ if you count micro-variants and local print differences.

Nothing in design history, not poster art, not propaganda, not banknotes, comes close in volume.

2. Over 10,000 issuers

Not just towns.

cities

factories

mines

banks

cafés

breweries

sports clubs

festivals

church groups

transportation companies

political groups

Somewhere around 5,000 to 10,000 different issuers total.

It’s the biggest decentralized design movement in history.

3. Notgeld was printed on everything

Not just paper.

linen

silk

leather

aluminium foil

wood

playing cards

coal dust

porcelain

sugar beet fibre

recycled documents

cardboard

sulfur

even old book pages

4. Some designs told full stories

A lot of Serienscheine sets were basically early graphic novels, 6, 8, 12 notes that illustrated a full narrative panel by panel.

5. A single town could issue 50+ sets

Some small towns released more artwork in two years than entire nations did in a decade.

6. Marketplace printing studios got so overloaded

Some print shops were running 24 hours a day, not to print money for survival, but to keep up with collectors.

7. Notgeld travelled more than people

Some notes moved hundreds of kilometers across Germany, even though they were only meant for one local area.

8. It accidentally trained a whole generation of German designers

Many who later worked in Bauhaus, poster design, publishing, and advertising started learning their craft designing Notgeld.

9. One of the biggest graphic archives in the world

Museums still discover new Notgeld designs today, literally notes nobody had ever recorded.

So it ends here, with me discovering all of this because I randomly picked up a few notes in a second-hand shop. I asked the seller what they were, and he just said he had no idea. Only later I realised they were forgotten pieces of a massive graphic design movement.